Moundville Archaeological Park

Archaeology At Moundville

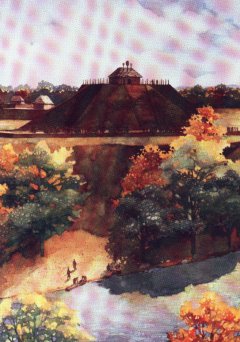

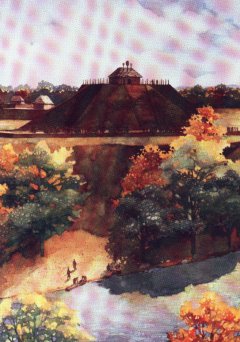

From A.D. 100 to 1500, Mississippian Indians constructed large

earthworks topped by temples, council houses, and the home of their nobility.

Moundville Archaeological Park contains more than two dozen of these surviving flat-topped

mounds, remnants of a ceremonial and economic center whose trade routes extended across

the entire southeastern United States. Today the park, located on the banks of the

Black Warrior River in Moundville, preserves 320 acres of what was once one of the largest

and most powerful prehistoric Native American communities in the Southeast.

The earliest recorded excavations at Moundville began in the

mid-19th century, with discoveries continuing into the 20th century. The largest

excavation at Moundville started in 1930 under the direction of Dr. Walter B. Jones, state

geologist and director of the Alabama Museum of Natural History. He enlisted the

service of the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, and under Jones' direction,

archaeological and building projects continued until 1942. During that time,

archaeologist excavated 45,000 square feet, uncovering 75 structures, 1,000 complete

ceramic vessels, and more than 25,000 pottery fragments.

Under the scrutiny of The University of Alabama and the

scientific community, archaeological investigations continue today at Moundville.

More than 100 years since the first excavations, Moundville still holds many secrets to

Alabama's prehistoric past and the Mississippian community that thrived there for 500

years.

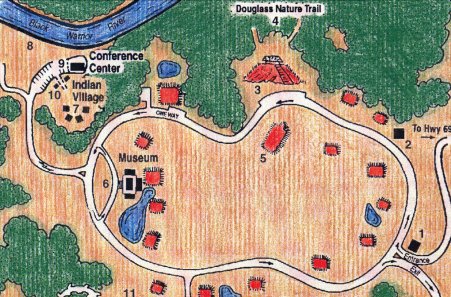

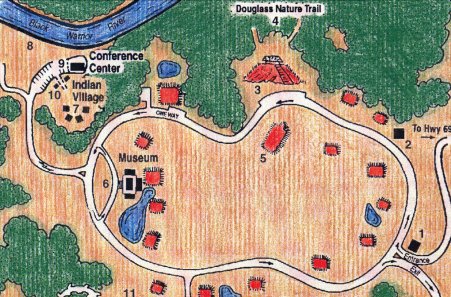

What To See At Moundville Today

Though portions of Moundville Archaeological Park are set

aside for re-creations of prehistoric life, much of the park exists in its natural state

and remains the best preserved site of its kind in the eastern United States.

A reconstructed temple sits on the summit of the Ceremonial

Mound, one of the tallest Mississippian mounds in the Southeast. This temple houses

a life-sized diorama of a religious ceremony. The Jones Archaeological Museum

displays the finest examples of Mississippian artwork recovered from the site, including

the Rattlesnake Disk, Alabama's official state artifact.

Winding through the park's wooded areas, the Douglass Nature

Trail meanders past native plants and flowers as well as two mounds preserved as they were

hundreds of years ago. Many wildflower varieties thrive at the park, particularly in

open areas and along the nature trail. A guide to Alabama's wildflowers is available

at the Jones Archaeological Museum.

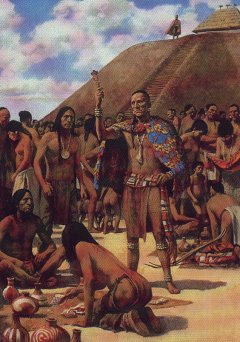

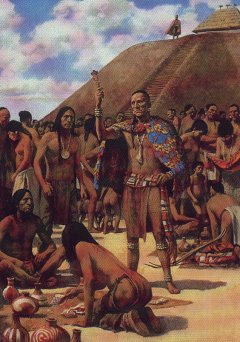

At the Indian village, life-sized models recreate the

dwellings and customs of the Moundville people. Throughout the year, local Native

Americans and museum staff host workshops and living history programs. Each summer,

the park and museum staff offer Indian culture and craft classes for adults and children.

Some students transform gourds into masks, bowls, or bottles; some weave their own

"dream catchers."

Each fall, the annual Moundville Native American Festival

draws thousands of people from Alabama and across the region, to celebrate the heritage of

southeastern Indians. Beginning the last Monday in September, the week long festival

features southeastern Native Americans performing traditional dances and songs, while

demonstrating artists teach and sell their crafts. Dressed in period clothing,

storytellers recall a time when people lived close to nature. Saturday, the final

day of the festival, is Indian Market Day, where artisans from across the region gather to

show and sell their wares. Native American dancing, singing, and sports events are

also featured on Saturday.

Prestige Goods and Mississippian Trade Economy

Trade was extremely important to Mississippian society.

The Moundville Indians bartered for imported goods up and down prehistoric trade routes

extending through eastern North America. Galena (a lead ore), quartz, steatite

(soapstone), marine shell, greenstone, mica, and copper were important raw materials, as

was beautiful pottery imported from Arkansas and elsewhere in the Southeast.

Archaeological investigations indicate that possession of these "prestige" goods

was restricted to the ruling class.

Trade not only brought rare materials from distant

places, but also served as an avenue for the exchange of ideas and customs. Prestige

goods may have also provided a means of maintaining political ties and the allegiance of

groups that paid tribute to the Moundville leaders.

The Univ. of Alabama's Museum of Natural History